Versiones de Alejandro Bajarlia

Enero, 2024

«La calle», de Stephen Dobyns (1941)

Versión de Alejandro Bajarlia

Diciembre, 2023

La calle

El carpintero atraviesa la calle con un tablón dorado

sobre el hombro, del mismo modo que lleva las cargas

de su vida. Vestido de blanco, su única debilidad es

la tentación. Ahora construye otra pared que lo proteja.

La pequeña niña persigue a su malcriada pelota roja, la golpea

una vez con su raqueta azul, la golpea otra vez. Tiene que

enseñarle las reglas que deben seguir las pelotas y le enloquece

ver que ella la mira con malicia, luego le guiña un ojo.

La pareja oriental quiere bailar siempre así:

dando vueltas en una calle concurrida, mientras él la sujeta

de la cintura, ella se desliza sobre una rodilla y la música se eleva

desde los adoquines: algunos días Ravel, algunos días Bizet.

La novicia que se marcha va cantando para ella misma.

Ha visto la salvación del mundo dormida en una cuna

que cuelga de un árbol. La canción de la muchacha crea

la luz del sol, crea la brisa que mece la cuna.

El panadero ha tenido media idea. Ahora se para como un pilar

en espera de otra. Mira la harina blanca caer como la nieve,

cubriendo a la gente que primero intenta caminar, luego gatear,

luego volverse formas redondas: muchas rebanadas de pan.

El bebe raptado por su cruel madre es muy viejo y durante años

protagonizó filmes silentes. Intenta explicar que por accidente

fue cambiado por un bebé en un autobús, pero no halla

las palabras mientras se lo llevan a darle otro horrible baño.

El obrero visionario conjura primero un gran salón,

luego se para en el escenario y explica, explica:

adónde va el sol por la noche, adónde vuelan las moscas en invierno,

un atento público de perros y gatos apiñados escucha en silencio.

Sin saber nada unas de otras, estas nueve personas se rodean

en una estrecha calle de la ciudad. Cada una se concentra

en sus pasos con tal atención que ninguna puede ver

al vecino a su alrededor, moviéndose en círculos

exactamente distintos, pero exactamente similares: vidas idénticas

que comenzaron solas, pasaron solas, acaban solas: tan separadas

como puntos de luz en un cielo nocturno, tan separadas

como estrellas y todo ese inmenso espacio oscuro entre ellas.

The Street*

Across the street, the carpenter carries a golden

board across one shoulder, much as he bears the burdens

of his life. Dressed in white, his only weakness is

temptation. Now he builds another wall to screen him.

The little girl pursues her bad red ball, hits it once

with her blue racket, hits it once again. She must

teach it the rules balls must follow and it turns her

quite wild to see how it leers at her, then winks.

The oriental couple wants always to dance like this:

swirling across a crowded street, while he grips

her waist and she slides to one knee and music rises

from cobblestones–some days Ravel, some days Bizet.

The departing postulant is singing to herself. She

has seen the world’s salvation asleep in a cradle,

hanging in a tree. The girl’s song makes

the sunlight, makes the breeze that rocks the cradle.

The baker’s had half a thought. Now he stands like a pillar

awaiting another. He sees white flour falling like snow,

covering people who first try to walk, then crawl,

then become rounded shapes: so many loaves of bread.

The baby carried off by his heartless mother is very old and

for years has starred in silent films. He tries to explain

he was accidentally exchanged for a baby on a bus, but he can

find no words as once more he is borne home to his awful bath.

First the visionary workman conjures a great hall, then

he puts himself on the stage, explaining, explaining:

where the sun goes at night, where flies go in winter, while

attentive crowds of dogs and cats listen in quiet heaps.

Unaware of one another, these nine people circle around

each other on a narrow city street. Each concentrates

so intently on the few steps before him, that not one

can see his neighbor turning in exactly different,

yet exactly similar circles around them: identical lives

begun alone, spent alone, ending alone–as separate

as points of light in a night sky, as separate as stars

and all that immense black space between them.

A propósito de Balthus

*Poema tomado del sitio The Poet Speaks of Art

«Paul Delvaux: El pueblo de las sirenas», Lisel Mueller (1924-2020)

Versión de Alejandro Bajarlia

Septiembre, 2023

Paul Delvaux: El pueblo de las sirenas

Óleo sobre lienzo, 1942

Lisel Mueller

¿Quién es ese hombre de negro que se aleja

de nosotros a la distancia?

Al pintor, dicen, le tomó mucho tiempo

encontrar su visión del mundo.

Las sirenas, si eso es lo que son

bajo esas faldas de cuerpo entero,

se sientan unas frente a otras

a lo largo de la calle, más bien un callejón,

delante de sus casas grises adosadas.

Todas se ven iguales, como una orden

de monjas rubias, o como prostitutas

de rostros castos, idénticos.

Qué tranquilas están, con sus ojos ausentes,

sus manos sobre regazos que nada revelan.

Sólo una tiene escamas en su vestido oscuro.

Es 1942; es Europa

y nada encaja. La única figura conocida

es el hombre de negro que se acerca al mar,

es pequeño y se está alejando de nosotros.

Paul Delvaux: The Village of the Mermaids*

Oil on canvas, 1942

Lisel Mueller

Who is that man in black, walking

away from us into the distance?

The painter, they say, took a long time

finding his vision of the world.

The mermaids, if that is what they are

under their full-length skirts,

sit facing each other

all down the street, more of an alley,

in front of their gray row houses.

They all look the same, like a fair-haired

order of nuns, or like prostitutes

with chaste, identical faces.

How calm they are, with their vacant eyes,

their hands in laps that betray nothing.

Only one has scales on her dusky dress.

It is 1942; it is Europe,

and nothing fits. The one familiar figure

is the man in black approaching the sea,

and he is small and walking away from us.

*Poema recuperado del sitio The Poet Speaks of Art

Breve video sobre Paul Delvaux

«Gótico estadounidense», John Stone (1936-2008)

Versión de Alejandro Bajarlia

Agosto, 2023

Gótico estadounidense

según la pintura de Grant Wood, 1930

John Stone

Justo afuera del marco

debe haber un perro,

pollos, vacas y paja

y un ahumadero

donde un jamón en nogal

también está en conserva

Aquí y por siempre

los bordes de la ventana gótica

anticipan los nervios

de la casa

las púas de la horquilla

reiteran el triunfo

del overol de él

y al frente y en el centro

las caras largas, los labios sobrios

sobre las erguidas columnas

de esta pareja

arrestada en nombre del arte

Los dos

para entonces

con el sol tan alto

deberían estar

en la hora mortal

de atender sus labores

En vez de eso permanecen ahí

dentro de la paciente tela

de las vidas que tejieron

él pregunta en silencio al artista

cuánto tiempo más

y se preocupa por la cosecha

ella también se preocupa por la cosecha

pero sobre todo en ese momento

si se acordó

de apagar la estufa.

American Gothic*

after the painting by Grant Wood, 1930

John Stone

Just outside the frame

there has to be a dog

chickens, cows and hay

and a smokehouse

where a ham in hickory

is also being preserved

Here for all time

the borders of the Gothic window

anticipate the ribs

of the house

the tines of the pitchfork

repeat the triumph

of his overalls

and front and center

the long faces, the sober lips

above the upright spines

of this couple

arrested in the name of art

These two

by now

the sun this high

ought to be

in mortal time

about their businesses

Instead they linger here

within the patient fabric

of the lives they wove

he asking the artist silently

how much longer

and worrying about the crops

she no less concerned about the crops

but more to the point just now

whether she remembered

to turn off the stove.

*Poema tomado del sitio The Poet Speaks of Art

Sobre American Gothic y Grant Wood

«Paisaje con la caída de Ícaro», de Pieter Brueghel, según William Carlos Williams y W. H. Auden

Versiones de Alejandro Bajarlia

Abril, 2023

William Carlos Williams (1883-1963)

Paisaje con la caída de Ícaro

Según Brueghel

cuando Ícaro cayó

era primavera

un labrador araba

su campo

todo el esplendor

del año estaba

despierto vibrando

cerca

de la orilla del mar

ocupado

consigo mismo

sudando bajo el sol

que derritió

la cera de las alas

insignificante

frente a la costa

hubo

un chapuzón casi inadvertido

era Ícaro

que se ahogaba

§

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus*

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

W. H. Auden (1907-1973)

Musée des Beaux Arts

Acerca del sufrimiento jamás se equivocaron

los antiguos Maestros: qué bien comprendieron

su lugar entre los humanos: cómo sobreviene

mientras alguien come, abre una puerta o da un aburrido paseo;

cómo, mientras los viejos aguardan con respeto y pasión

el nacimiento milagroso, siempre habrá

niños que no querían que ocurriera, mientras patinan

sobre un estanque a la orilla del bosque:

jamás olvidaron

que aun el terrible martirio debe seguir su curso

de algún modo, en un rincón, en algún lugar sórdido

donde los perros llevan su vida de perros y el caballo del verdugo

se rasca las inocentes grupas contra un árbol.

Por ejemplo, en el Ícaro de Brueghel: con qué parsimonia

se aparta todo del desastre; quizá el labrador

haya escuchado el salpicar del agua, el grito desamparado,

sin embargo, para él no fue una desgracia relevante; el sol brillaba

como siempre, cayendo sobre las piernas blancas que desaparecían

en las verdes aguas, y el suntuoso barco que debía haber visto

algo asombroso, un muchacho que caía del cielo,

tenía que llegar a su destino y siguió navegando con calma.

§

Musee des Beaux Arts*

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

*Poemas tomados del sitio The Poet Speaks of Art.

Lectura de «Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (y «This Is Just to Say»), de William Carlos Williams.

W. H. Auden lee «Musee des Beaux Arts».

Poemas de Charles Simic (1938-2023)

Versiones de Alejandro Bajarlia

Diciembre de 2022

Imperio de los sueños

En la primera página de mi diario de sueños

siempre está anocheciendo

en un país ocupado.

La hora previa al toque de queda.

Una pequeña ciudad provincial.

Todas las casas a oscuras.

Los escaparates destruidos.

Estoy en la esquina de una calle

donde no debería estar.

Solo y sin abrigo

he salido a buscar

un perro negro que responde a mi silbido.

Tengo una especie de máscara de Halloween

que me da miedo ponerme.

§

Empire of Dreams*

On the first page of my dreambook

It’s always evening

In an occupied country.

Hour before the curfew.

A small provincial city.

The houses all dark.

The storefronts gutted.

I am on a street corner

Where I shouldn’t be.

Alone and coatless

I have gone out to look

For a black dog who answers to my whistle.

I have a kind of Halloween mask

Which I am afraid to put on.

Llegada tardía

El mundo ya estaba aquí,

sereno en su otredad.

Sólo te bastó llegar

en el demorado tren de la tarde

a donde nadie te esperaba.

Un pueblo que nunca nadie recordó

debido a su monotonía,

donde perdiste el rumbo

buscando un lugar para hospedarte

en un laberinto de calles idénticas.

Fue entonces que escuchaste,

como por vez primera,

el sonido de tus propios pasos

bajo el reloj de una iglesia,

el cual se detuvo al mismo tiempo que tú

entre dos calles vacías,

radiantes bajo la luz solar de la tarde,

dos modestos tramos del infinito

dispuestos para asombrarte

antes de reanudar tu camino.

§

Late Arrival*

The world was already here,

Serene in its otherness.

It only took you to arrive

On the late afternoon train

To where no one awaited you.

A town no one ever remembered

Because of its drabness,

Where you lost your way

Searching for a place to stay

In a maze of identical streets.

It was then that you heard,

As if for the very first time,

The sound of your own footsteps

Under a church clock

Which had stopped just as you did

Between two empty streets

Aglow in the afternoon sunlight,

Two modest stretches of infinity

For you to wonder at

Before resuming your walk.

Hotel Insomnio

Me gustaba aquel rinconcito,

con su ventana que daba a un muro de ladrillos.

En el cuarto de al lado había un piano.

Una que otra noche al mes

un anciano lisiado llegaba a tocar

“My Blue Heaven”.

Pero era, sobre todo, un lugar tranquilo.

Cada cuarto tenía una araña de pesado abrigo

que atrapaba una mosca con su telaraña

de humo de cigarrillo y de ensueño.

Tan oscuro,

no me veía la cara en el espejo del baño.

A las 5 a.m. el sonido de pies descalzos arriba.

La “Gitana” vidente,

cuyo local está en la esquina,

iba a hacer pipí tras una noche de amor.

Alguna vez, también, se oyó el sollozo de un niño.

Tan cercano que pensé,

por un momento, que era yo quien sollozaba.

§

Hotel Insomnia*

I liked my little hole,

Its window facing a brick wall.

Next door there was a piano.

A few evenings a month

a crippled old man came to play

«My Blue Heaven.»

Mostly, though, it was quiet.

Each room with its spider in heavy overcoat

Catching his fly with a web

Of cigarette smoke and revery.

So dark,

I could not see my face in the shaving mirror.

At 5 A.M. the sound of bare feet upstairs.

The «Gypsy» fortuneteller,

Whose storefront is on the corner,

Going to pee after a night of love.

Once, too, the sound of a child sobbing.

So near it was, I thought

For a moment, I was sobbing myself.

Feria de pueblo

para Hayden Carruth

Si no viste al perro de seis patas,

no importa.

Nosotros sí, y se la pasó echado en un rincón.

En cuanto a las patas extras,

te habituabas rápido a ellas

y pensabas en otra cosa.

Algo así: qué noche tan oscura y fría

para andar en la feria.

Luego el guardia lanzó un palo

y el perro fue por él

en cuatro patas, las otras dos aleteaban detrás,

lo cual hizo llorar de risa a una muchacha.

Estaba borracha, también el hombre

que no dejaba de besarle el cuello.

El perro recogió el palo y volteó a mirarnos.

Y ese fue todo el espectáculo.

§

Country Fair*

for Hayden Carruth

If you didn’t see the six-legged dog,

It doesn’t matter.

We did, and he mostly lay in the corner.

As for the extra legs,

One got used to them quickly

And thought of other things.

Like, what a cold, dark night

To be out at the fair.

Then the keeper threw a stick

And the dog went after it

On four legs, the other two flapping behind,

Which made one girl shriek with laughter.

She was drunk and so was the man

Who kept kissing her neck.

The dog got the stick and looked back at us.

And that was the whole show.

Tenedor

Esa cosa extraña debió haberse arrastrado

desde el mismo infierno.

Se parece a la pata de un pájaro

que cuelga del cuello de un caníbal.

Mientras lo sostienes en la mano,

mientras apuñalas con él un pedazo de carne,

es posible imaginar el resto del pájaro:

su cabeza, como tu puño,

es grande, calva, sin pico y ciega.

§

Fork*

This strange thing must have crept

Right out of hell.

It resembles a bird’s foot

Worn around the cannibal’s neck.

As you hold it in your hand,

As you stab with it into a piece of meat,

It is possible to imagine the rest of the bird:

Its head which like your fist

Is large, bald, beakless, and blind.

La explicación parcial

Parece que fue hace mucho tiempo

cuando el mesero me tomó la orden.

Una pequeña cafetería mugrienta,

afuera está nevando.

Parece que está más oscuro

desde la última vez que oí la puerta

de la cocina a mi espalda,

desde la última vez que vi

a alguien pasar por la calle.

Un vaso de agua con hielos

me guarda compañía

en esta mesa que yo mismo elegí

al entrar.

Y un anhelo,

un increíble anhelo

de husmear en

la conversación

de los cocineros.

§

The Partial Explanation*

Seems like a long time

Since the waiter took my order.

Grimy little luncheonette,

The snow falling outside.

Seems like it has grown darker

Since I last heard the kitchen door

Behind my back

Since I last noticed

Anyone pass on the street.

A glass of ice-water

Keeps me company

At this table I chose myself

Upon entering.

And a longing,

Incredible longing

To eavesdrop

On the conversation

Of cooks.

Un libro lleno de imágenes

Mi padre estudiaba teología por correo

y estaba haciendo su examen.

Mi madre tejía. Yo me senté en silencio con un libro

lleno de imágenes. Caía la noche.

Las manos se me enfriaron tocando los rostros

de reyes y reinas muertos.

Había un abrigo negro

en la habitación de arriba

meciéndose en el techo,

pero ¿qué hacía ahí?

Las largas agujas de mi madre formaban rápidas cruces.

Eran negras

como el interior de mi cabeza en ese momento.

Las páginas que iba cambiando sonaban como alas.

“El alma es un ave”, dijo él de repente.

En mi libro lleno de imágenes

una furiosa batalla: lanzas y espadas

formaban una especie de bosque invernal,

mi corazón clavado sangraba en sus ramas.

§

A Book Full of Pictures*

Father studied theology through the mail

And this was exam time.

Mother knitted. I sat quietly with a book

Full of pictures. Night fell.

My hands grew cold touching the faces

Of dead kings and queens.

There was a black raincoat

in the upstairs bedroom

Swaying from the ceiling,

But what was it doing there?

Mother’s long needles made quick crosses.

They were black

Like the inside of my head just then.

The pages I turned sounded like wings.

«The soul is a bird,» he once said.

In my book full of pictures

A battle raged: lances and swords

Made a kind of wintry forest

With my heart spiked and bleeding in its branches.

Lee tu destino

Un mundo está desapareciendo.

Pequeña calle,

eras demasiado estrecha,

ya estabas demasiado a la sombra.

Sólo tuviste un perro,

un niño solitario.

Ocultaste el más grande de tus espejos,

a tus desnudos amantes.

Alguien se los llevó

en un camión abierto.

Aún estaban desnudos, viajaban

sentados en el sofá

sobre una planicie oscura

y desconocida de Kansas o Nebraska

donde se fraguaba una tormenta.

La mujer abrió un paraguas rojo

en el camión. El niño

y el perro corrían detrás de ellos,

como detrás de un gallo

con la cabeza cercenada.

§

Read Your Fate*

A world’s disappearing.

Little street,

You were too narrow,

Too much in the shade already.

You had only one dog,

One lone child.

You hid your biggest mirror,

Your undressed lovers.

Someone carted them off

In an open truck.

They were still naked, travelling

On their sofa

Over a darkening plain,

Some unknown Kansas or Nebraska

With a storm brewing.

The woman opening a red umbrella

In the truck. The boy

And the dog running after them,

As if after a rooster

With its head chopped off.

Poema sin título

Le digo al plomo

¿Por qué permitiste

ser puesto en una bala?

¿Has olvidado a los alquimistas?

¿Has renunciado a la esperanza

de convertirte en oro?

Nadie responde.

Plomo. Bala. Con nombres

como esos

el sueño es profundo y largo.

§

Poem without a Title*

I say to the lead

Why did you let yourself

Be cast into a bullet?

Have you forgotten the alchemists?

Have you given up hope

In turning into gold?

Nobody answers.

Lead. Bullet. With names

Such as these

The sleep is deep and long.

La habitación blanca

Lo obvio es difícil

de comprobar. Muchos prefieren

lo oculto. Yo lo prefería, también.

Escuchaba los árboles.

Tenían un secreto

que estaban a punto de

contarme…

Y no lo hicieron.

Llegó el verano. Cada árbol

de mi calle tenía su propia

Sherezada. Mis noches

eran parte de las locas historias

que contaban. Entrábamos

en casas oscuras,

siempre más casas oscuras,

calladas, abandonadas.

Había alguien con los ojos cerrados

en los pisos superiores.

El temor a eso, y el asombro,

me impedían dormir.

La verdad es calva y fría,

decía la mujer

que vestía siempre de blanco.

No salía de su habitación.

El sol apuntaba hacia algunas

cosas que habían sobrevivido

la larga noche, intactas.

Las cosas más ordinarias,

difíciles por su obviedad.

No hacían ruido.

Era la clase de día

que la gente llamaba “perfecto”.

¿Los dioses se disfrazaban

de pasadores negros, de espejo de mano,

de peine sin diente?

¡No! No era así.

Sólo las cosas tal como son,

impasibles, mudas, reposando

bajo esa luz radiante…

y los árboles esperando la noche.

§

The White Room*

The obvious is difficult

To prove. Many prefer

The hidden. I did, too.

I listened to the trees.

They had a secret

Which they were about to

Make known to me—

And then didn’t.

Summer came. Each tree

On my street had its own

Scheherazade. My nights

Were a part of their wild

Storytelling. We were

Entering dark houses,

Always more dark houses,

Hushed and abandoned.

There was someone with eyes closed

On the upper floors.

The fear of it, and the wonder,

Kept me sleepless.

The truth is bald and cold,

Said the woman

Who always wore white.

She didn’t leave her room.

The sun pointed to one or two

Things that had survived

The long night intact.

The simplest things,

Difficult in their obviousness.

They made no noise.

It was the kind of day

People described as «perfect.»

Gods disguising themselves

As black hairpins, a hand-mirror,

A comb with a tooth missing?

No! That wasn’t it.

Just things as they are,

Unblinking, lying mute

In that bright light—

And the trees waiting for the night.

Donde oscurecía

Sobre el camino de álamos ondulados,

en una región llana y desolada

hacia el lejano y gris horizonte, donde oscurecía,

un hombre y una mujer andaban a pie,

cada uno cargaba una maleta pequeña.

Estaban cansados y se habían quitado

los zapatos para seguir caminando

sobre sus dedos, mirando hacia delante.

A cada momento pasaban rápidos los autos,

mientras ellos se habituaban a ese trecho de

camino, vacío como el cuervo que vuela,

qué rápido desaparecían…

es decir, los autos, y luego la llovizna

que trajo el temprano anochecer,

poco a poco, una exigua luz

en algún lugar, y luego ni siquiera eso.

§

Wherein obscurely*

On the road with billowing poplars,

In a country flat and desolate

To the far-off gray horizon, wherein obscurely,

A man and a woman went on foot,

Each carrying a small suitcase.

They were tired and had taken off

Their shoes and were walking on

Their toes, staring straight ahead.

Every time a car passed fast,

As they’re wont to on such a stretch of

Road, empty as the crow flies,

How quickly they were gone–

The cars, I mean, and then the drizzle

That brought on the early evening,

Little by little, and hardly a light

Anywhere, and then not even that.

Charles Simic lee poemas de su libro Selected Poems

*Poemas de Charles Simic en Best Poems Encyclopedia

«Muerte en el bar», de Vernon Scannell

Versión de Alejandro Bajarlia

Octubre, 2022

Muerte en el bar

El bar donde entró no era

un lugar que visitara a menudo

y recibió con agrado el anonimato.

Nadie encendía aparatos

inquisitivos, nadie podía

ni quería ver con exactitud lo que

él era, había sido o sería;

un lugar tranquilo, pardo, un lugar para beber

y dejar las ideas hervir a fuego lento como un buen caldo,

sin la distracción de los espejos, sin nada de grasas,

sin el rostro calculador del reloj,

un buen lugar sereno para beber y pensar.

Si acaso alguien notaba

que estaba ahí, verían

a un hombre más bien alto y delgado,

de cabello claro, ojos azules y guapo

de una forma estrictamente masculina.

No sabrían, ni querrían saber,

más de lo que veían en él,

ni pondrían micrófonos ocultos

en las paredes del cráneo para escuchar

cualquiera de los murmullos

que repican con sigilo en esa oscuridad:

un excelente sitio para tomar a sorbitos una ginebra.

Luego… ¡el piquete de la interrupción! La voz

penetró las paredes secretas y sacudió

su reflexiva calma con un impacto sutil.

Un mesero, de rostro blanco como servilleta

y cabello brillante como punta de zapato, se disculpó

por la engominada intrusión y preguntó

si su nombre era el que en efecto era.

En tal caso, tenía una llamada en

el teléfono que usaban los clientes,

el que está junto al sanitario de los caballeros. Él acudió.

En la calidez de la discreta cabina,

escuchó la voz de su esposa, estrangulada por

la distancia, la oscuridad y los rollos de cable,

aunque sin duda era la voz de ella,

quien le preguntó por qué tardaba tanto,

por qué la humillaba

en todas las formas posibles,

por qué le hacía la vida tan difícil.

Había llamado a casi todos los bares de la ciudad

antes de que por fin pudiera localizarlo.

Él dijo que estuvo trabajando hasta tarde

y pasó rápido a tomarse un trago en

su extenuante camino a casa. Regresaría

enseguida. Justo en ese momento. De inmediato.

No, ni una gota más. Ni una.

De regreso al bar, se tomó la ginebra

y ordenó una más, sólo una, la última.

Mejor así: la paz lo había abandonado;

ya no se sentía bienvenido en ese lugar.

Vio pasar por ahí al mesero,

aquel pálido embajador de la tristeza,

lo llamó y le preguntó cómo

había distinguido al cliente

que llamaban por teléfono.

El mesero dijo: “Su esposa lo describió,

señor. Lo reconocí al instante”.

“¿Y cómo me describió para

que me reconociera tan fácilmente?”.

“Dijo que vestía traje gris, camisa crema, corbata azul,

que era más o menos alto, de cara colorada,

rechoncho, de mediana edad y casi calvo”.

La incredulidad gritó al instante y se quedó

rígida en el asiento, luego cayó muerta.

“Rechoncho, mediana edad, casi calvo”.

El esbelto fantasma de cabello dorado

lo miró salir a la intemperie

fría y oscura, escuchó sus lentos pasos disiparse

al caminar rumbo a su esposa, al sillón, a la cama.

***

Death in The Lounge Bar*

The bar he went inside was not

A place he often visited;

He welcomed anonymity;

No one to switch inquisitive

Receivers on, no one could see,

Or wanted to, exactly what

He was, or had been, or would be;

A quiet brown place, a place to drink

And let thought simmer like good stock,

No mirrors to distract, no fat

And calculating face of clock,

A good calm place to sip and think.

If anybody noticed that

He was even there they’d see

A fairly tall and slender man,

Fair-haired, blue-eyed, and handsome in

A manner strictly masculine.

They would not know, or want to know,

More than what they saw of him,

Nor would they wish to bug the bone

Walls of skull and listen in

To whatever whisperings

Pittered quietly in that dark:

An excellent place to sip your gin.

Then—sting of interruption! voice

Pierced the private walls and shook

His thoughtful calm with delicate shock.

A waiter, with white napkin face

And shining toe-cap hair, excused

The oiled intrusion, asking if

His name was what indeed it was.

In that case he was wanted on

The telephone the customers used,

The one next to the Gents. He went.

Inside the secretive warm box

He heard his wife’s voice, strangled by

Distance, darkness, coils of wire,

But unmistakably her voice,

Asking why he was so late,

Why did he humiliate

Her in every way he could,

Make her life so hard to face?

She’d telephoned most bars in town

Before she’d finally tracked him down.

He said that he’d been working late

And slipped in for a quick one on

His weary journey home. He’d come

Back at once. Right now. Toot sweet.

No, not another drop. Not one.

Back in the bar, he drank his gin

And ordered just one more, the last.

And just as well: his peace had gone;

The place no longer welcomed him.

He saw the waiter moving past,

That pale ambassador of gloom,

And called him over, asked him how

He had known which customer

To summon to the telephone.

The waiter said, ‘Your wife described

You, sir. I knew you instantly.’

‘And how did she describe me, then,

That I’m so easily recognized?’

‘She said: grey suit, cream shirt, blue tie,

That you were fairly tall, red-faced,

Stout, middle-aged, and going bald.’

Disbelief cried once and sat

Bolt upright, then it fell back dead.

‘Stout middle-aged and going bald.’

The slender ghost with golden hair

Watched him go into the cold

Dark outside, heard his slow tread

Fade towards wife, armchair, and bed.

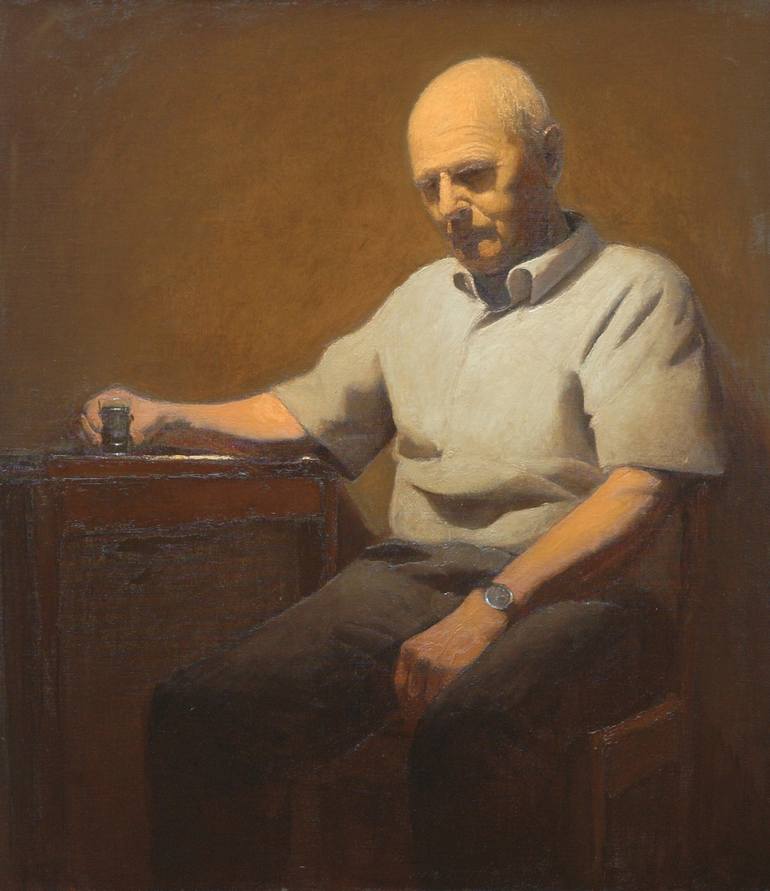

Old Man with a Drink (2011), Jan Zetstra

Lectura de «Death in the Lounge Bar»

*Tomado de Best-Poems.net

Poemas de Leonard Cohen (1934-2016)

Versiones de Alejandro Bajarlia

Mayo-Junio, 2022

El único poema

Este es el único poema

que puedo leer

yo soy el único

que puede escribirlo

no me suicidé

cuando las cosas salieron mal

no recurrí

a las drogas ni a la docencia

intenté dormir

pero cuando no podía dormir

aprendí a escribir

aprendí a escribir

lo que podría leer

en noches como esta

alguien como yo

§

The Only Poem*

This is the only poem

I can read

I am the only one

can write it

I didn’t kill myself

when things went wrong

I didn’t turn

to drugs or teaching

I tried to sleep

but when I couldn’t sleep

I learned to write

I learned to write

what might be read

on nights like this

by one like me

Me pregunto cuánta gente de esta ciudad

Me pregunto cuánta gente de esta ciudad

vive en cuartos amueblados.

En la madrugada, cuando miro los edificios,

juro que veo un rostro en cada ventana

devolviéndome la mirada

y cuando me alejo

me pregunto cuántos vuelven a sus escritorios

y escriben esto.

§

I Wonder How Many People in This City*

I wonder how many people in this city

live in furnished rooms.

Late at night when I look out at the buildings

I swear I see a face in every window

looking back at me

and when I turn away

I wonder how many go back to their desks

and write this down.

Una noche quemé la casa que amaba

Una noche quemé la casa que amaba,

irradió un círculo perfecto

en el que vi algunos hierbajos y piedra

y más allá: no cualquier cosa.

Ciertas criaturas del aire

asustadas por la noche

se acercaron a ver el mundo otra vez

y perecieron en la luz.

Ahora navego de cielo en cielo

y toda la negrura canta

contra el barco que he construido

con alas mutiladas.

§

One Night I Burned the House I Loved*

One night I burned the house I loved,

It lit a perfect ring

In which I saw some weeds and stone

Beyond—not anything.

Certain creatures of the air

Frightened by the night

They came to see the world again

And perished in the light.

Now I sail from sky to sky

And all the blackness sings

Against the boat that I have made

Of mutilated wings.

Poema

Escuché de un hombre

que dice las palabras con tal belleza

que con sólo pronunciar sus nombres

las mujeres se entregan a él.

Si soy torpe junto a tu cuerpo

mientras el silencio brota como tumores en nuestros labios,

es porque escucho un hombre subir las escaleras y aclararse la garganta al otro lado de la puerta.

§

Poem*

I heard of a man

who says words so beautifully

that if he only speaks their name

women give themselves to him.

If I am dumb beside your body

while silence blossoms like tumors on our lips,

it is because I hear a man climb stairs and clear his throat outside the door.

El siguiente

Las cosas son mejores en Milán.

Las cosas son mucho mejores en Milán.

Mi aventura se ha dulcificado.

Conocí a una muchacha y a un poeta.

Uno de ellos ha muerto

y uno de ellos está vivo.

El poeta era de Perú

y la muchacha era doctora.

Ella tomaba antibióticos.

Nunca la olvidaré.

Me llevó a una iglesia oscura

consagrada a María.

Vivan los caballos y las monturas.

El poeta me devolvió el espíritu

que había perdido al rezar.

Era un gran hombre que venía de la guerra civil.

Dijo que su muerte estaba en mis manos

porque yo era el siguiente

en explicar la debilidad del amor.

El poeta era César Vallejo

quien yace en el suelo de su frente.

Acompáñame ahora, gran guerrero,

cuya fuerza sólo dependía

de los favores de una mujer.

§

The Next One*

Things are better in Milan.

Things are a lot better in Milan.

My adventure has sweetened.

I met a girl and a poet.

One of them was dead

and one of them was alive.

The poet was from Peru

and the girl was a doctor.

She was taking antibiotics.

I will never forget her.

She took me into a dark church

consecrated to Mary.

Long live the horses and the saddles.

The poet gave me back my spirit

which I had lost in prayer.

He was a great man out of the civil war.

He said his death was in my hands

because I was the next one

to explain the weakness of love.

The poet was Cesar Vallejo

who lies at the floor of his forehead.

Be with me now great warrior

whose strength depends solely

on the favours of a woman.

Canción

Casi me fui a dormir

sin recordar

las cuatro violetas blancas

que puse en el ojal

de tu suéter verde

y cómo te besé después

y tú me besaste

con timidez como si

nunca hubiera sido tu amante

§

Song*

I almost went to bed

without remembering

the four white violets

I put in the button-hole

of your green sweater

and how I kissed you then

and you kissed me

shy as though I’d

never been your lover

Siempre estoy pensando en una canción

Siempre estoy pensando en una canción

para que Anjani cante

Será sobre nuestra vida juntos

Será muy ligera o muy profunda

pero nada a medias

Yo escribiré la letra

y ella escribirá la melodía

Yo no seré capaz de cantarla

porque se elevará muy alto

Ella la cantará bellamente

y yo corregiré su canto

y ella corregirá mi escritura

hasta hacerla más que bella

Luego la escucharemos

no a menudo

no siempre juntos

sino de vez en cuando

por el resto de nuestras vidas

§

I’m Always Thinking of a Song**

I’m always thinking of a song

For Anjani to sing

It will be about our lives together

It will be very light o very deep

But nothing in between

I will write the words

And she will write the melody

I won’t be able to sing it

Because it will climb too high

She will sing it beautifully

And I’ll correct her singing

And she’ll correct my writing

Until it is better than beautiful

Then we’ll listen to it

Not often

Not always together

But now and then

For the rest of our lives

Dueño de todo

Te preocupa que te deje.

Nunca te dejaré.

Sólo los extraños viajan.

Siendo dueño de todo,

no tengo adónde ir.

§

Owning Everything*

You worry that I will leave you.

I will not leave you.

Only strangers travel.

Owning everything

I have nowhere to go.

No tienes que amarme

No tienes que amarme

sólo porque

eres todas las mujeres

que siempre he deseado

Nací para seguirte

cada noche

mientras aún sea

los muchos hombres que te aman

Te encuentro ante una mesa

Tomo tu puño entre mis manos

en un taxi solemne

Despierto solo

con mi mano sobre tu ausencia

en el Hotel Disciplina

Escribí todas esas canciones para ti

Hice arder velas rojas y negras

con las formas de un hombre y una mujer

Me casé con el humo

de dos pirámides de sándalo

Recé por ti

Recé para que me amaras

y para que no me amaras

§

You Do Not Have to Love Me*

You do not have to love me

just because

you are all the women

I have ever wanted

I was born to follow you

every night

while I am still

the many men who love you

I meet you at a table

I take your fist between my hands

in a solemn taxi

I wake up alone

my hand on your absence

in Hotel Discipline

I wrote all these songs for you

I burned red and black candles

shaped like a man and a woman

I married the smoke

of two pyramids of sandalwood

I prayed for you

I prayed that you would love me

and that you would not love me

Regalo

Me dices que el silencio

está más cerca de la paz que los poemas

pero si de regalo

te trajera silencio

(pues conozco el silencio)

tú dirías

Esto no es silencio

esto es otro poema

y me lo devolverías.

§

Gift*

You tell me that silence

is nearer to peace than poems

but if for my gift

I brought you silence

(for I know silence)

you would say

This is not silence

this is another poem

and you would hand it back to me.

En el camino

para C. C.

En el camino de la soledad

llegué al lugar de la canción

y me quedé ahí

la mitad de mi vida

Ahora dejo mi guitarra

y mis teclados

mis amigos y mis compañeras de s-o

y salgo tropezando de nuevo

al camino de la soledad

Soy viejo pero no me arrepiento

de nada

a pesar de estar enojado y solo

y colmado de miedo y deseo

Inclínate hacia mí

desde tu neblina y tus vides

oh, espigada de largos dedos

y profunda mirada

Inclínate hacia este saco de veneno

y dientes podridos

y empuja tus labios

a la luz de mi corazón

§

On the Path*

for C. C.

On the path of loneliness

I came to the place of song

and tarried there

for half my life

Now I leave my guitar

and my keyboards

my friends and my s-x companions

and I stumble out again

on the path of loneliness

I am old but I have no regrets

not one

even though I am angry and alone

and filled with fear and desire

Bend down to me

from your mist and vines

O high one, long-fingered

and deep-seeing

Bend down to this sack of poison

and rotting teeth

and press your lips

to the light of my heart

Hay

una grieta

en todo.

Así es cómo

entra

la luz.

§

There is

a crack

in everything.

That’s how

the light

gets in.

Leonard Cohen lee su poesía

*Colección de poemas de Leonard Cohen

**Leonard Cohen, The Flame. Poems, Notebooks, Lyrics, Drawings. Eds. Robert Faggen y Alexandra Pleshoyano. Nueva York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018.

Poemas de Theodore Roethke (1908-1963)

Versiones de Alejandro Bajarlia

Febrero-Marzo, 2022

Lo mínimo

Estudio las vidas en una hoja: los pequeños

durmientes, enzimas entumidas en frías dimensiones,

escarabajos en cuevas, tritones, sordos peces,

piojos atados a hierbas largas, flácidas, subterráneas,

larvas en pantanos

y bacterias trepadoras

que se retuercen en heridas

como angulas en estanques,

con bocas lánguidas que besan las cálidas suturas,

limpiando y acariciando,

reptando y curando.

§

The Minimal*

I study the lives on a leaf: the little

Sleepers, numb nudgers in cold dimensions,

Beetles in caves, newts, stone-deaf fishes,

Lice tethered to long limp subterranean weeds,

Squirmers in bogs,

And bacterial creepers

Wriggling through wounds

Like elvers in ponds,

Their wan mouths kissing the warm sutures,

Cleaning and caressing,

Creeping and healing.

Dolor

He conocido la inexorable tristeza de los lápices,

ordenados en sus cajas, el dolor de la libreta y el peso del papel,

toda la pena de las carpetas de manila y del mucílago,

la desolación de espacios públicos inmaculados,

la sala de recepción solitaria, el sanitario, el conmutador,

el patetismo inalterable del lavabo y de la jarra,

el ritual del multígrafo, el clip del papel, la coma,

la interminable duplicación de vidas y objetos.

Y he visto el polvo en los muros de instituciones,

más fino que la harina, vivo, más peligroso que la sílice,

tamizado, casi invisible, durante largas tardes de tedio,

soltando una fina capa sobre uñas y cejas delicadas, glaseando

el pálido cabello, los rostros duplicados, grises, ordinarios.

§

Dolor*

I have known the inexorable sadness of pencils,

Neat in their boxes, dolor of pad and paper weight,

All the misery of manilla folders and mucilage,

Desolation in immaculate public places,

Lonely reception room, lavatory, switchboard,

The unalterable pathos of basin and pitcher,

Ritual of multigraph, paper-clip, comma,

Endless duplicaton of lives and objects.

And I have seen dust from the walls of institutions,

Finer than flour, alive, more dangerous than silica,

Sift, almost invisible, through long afternoons of tedium,

Dropping a fine film on nails and delicate eyebrows,

Glazing the pale hair, the duplicate grey standard faces.

Despensa en el sótano

Nada dormía en ese sótano, húmedo como una zanja,

los tubérculos huían de las cajas rastreando grietas en la oscuridad,

los capullos colgaban y desfallecían,

pendiendo obscenamente de cajones mohosos,

largos cuellos caídos, amarillos, malvados, como serpientes tropicales.

¡Y vaya congreso de hedores!

Las raíces maduran como carnada vieja,

tallos pulposos, rancios, abundantes en los silos,

moho de hojas, estiércol, limo, acumulados en tablones viscosos.

Nada renunciaba a la vida:

aun la suciedad seguía exhalando un leve aliento.

§

Root Cellar*

Nothing would sleep in that cellar, dank as a ditch,

Bulbs broke out of boxes hunting for chinks in the dark,

Shoots dangled and drooped,

Lolling obscenely from mildewed crates,

Hung down long yellow evil necks, like tropical snakes.

And what a congress of stinks!

Roots ripe as old bait,

Pulpy stems, rank, silo-rich,

Leaf-mold, manure, lime, piled against slippery planks.

Nothing would give up life:

Even the dirt kept breathing a small breath.

Macabro epidérmico

Descortés es aquel que aborrece

el aspecto de su ropa carnal:

la tela volátil cosida a los huesos,

las vestiduras del esqueleto,

el traje que no es pelaje ni pelo,

el capote de maldad y desesperación,

el velo tantas veces violado por

las caricias de la mano y la mirada.

Pero tal es mi falta de decoro:

odio mi atuendo epidérmico,

la obscenidad de la sangre salvaje,

los andrajos de mi anatomía,

y por voluntad propia me despojaría

de los falsos accesorios del sentido,

para dormir sin pudicia, un fantasma

muy encarnado y carnal.

§

Epidermal Macabre*

Indelicate is he who loathes

The aspect of his fleshy clothes—

The flying fabric stitched on bone,

The vesture of the skeleton,

The garment neither fur nor hair,

The cloak of evil and despair,

The veil long violated by

Caresses of the hand and eye.

Yet such is my unseemliness:

I hate my epidermal dress,

The savage blood’s obscenity,

The rags of my anatomy,

And willingly would I dispense

With false accouterments of sense,

To sleep immodestly, a most

Incarnadine and carnal ghost.

Viva la maleza

¡Viva la maleza que abruma

mi estrecho reino vegetal!:

la roca amarga, el suelo árido,

que obligan al hijo del hombre a trabajar;

todas las cosas profanas, marcadas

por la maldición, lo feo del universo.

Lo áspero, lo retorcido y lo salvaje,

que mantienen el espíritu inmaculado.

Con ellos combino mi poco ingenio

y me gano el derecho a levantarme o a sentarme.

Tener esperanza, mirar, crear, o beber y morir:

ellos forman la criatura que soy.

§

Long Live the Weeds*

Long live the weeds that overwhelm

My narrow vegetable realm!—

The bitter rock, the barren soil

That force the son of man to toil;

All things unholy, marked by curse,

The ugly of the universe.

The rough, the wicked, and the wild

That keep the spirit undefiled.

With these I match my little wit

And earn the right to stand or sit.

Hope, look, create, or drink and die:

These shape the creature that is I.

El sobreviviente

Tengo veinticuatro años

fui llevado a la masacre

sobreviví.

Los siguientes son sinónimos vacíos:

hombre y bestia

amor y odio

amigo y enemigo

oscuridad y luz.

El modo de matar hombres y bestias es el mismo

lo he visto:

camiones llenos de hombres mutilados

que no serán salvados.

Las ideas son sólo palabras:

virtud y crimen

verdad y mentiras

belleza y fealdad

valentía y cobardía.

La virtud y el crimen pesan lo mismo

lo he visto:

en un hombre que era a la vez

criminal y virtuoso.

Busco un profesor y maestro

que restaure mi visión, mi oído, mi discurso

que vuelva a nombrar los objetos y las ideas

que separe la oscuridad de la luz.

Tengo veinticuatro años

fui llevado a la masacre

sobreviví.

§

The Survivor*

I am twenty-four

led to slaughter

I survived.

The following are empty synonyms:

man and beast

love and hate

friend and foe

darkness and light.

The way of killing men and beasts is the same

I’ve seen it:

truckfuls of chopped-up men

who will not be saved.

Ideas are mere words:

virtue and crime

truth and lies

beauty and ugliness

courage and cowardice.

Virtue and crime weigh the same

I’ve seen it:

in a man who was both

criminal and virtuous.

I seek a teacher and a master

may he restore my sight hearing and speech

may he again name objects and ideas

may he separate darkness from light.

I am twenty-four

led to slaughter

I survived.

La flor del geranio

Cuando la puse, una vez, junto al bote de basura,

lucía tan débil y desaliñada,

tan ingenua y confiada, como un caniche enfermo

o un áster marchito a finales de septiembre,

que la volví a meter

para renovar la rutina:

vitaminas, agua, cualquier

sustento parecía prudente

en aquel entonces: había vivido tanto tiempo

de ginebra, pasadores, puros a medio fumar, cerveza pasada,

que sus pétalos marchitos caían

sobre la alfombra desteñida, la grasa

rancia del bistec se pegaba a sus hojas velludas.

(Reseca, crujía como un tulipán).

¡Las cosas que sobrevivió!:

las damas tontas que chillaban durante la noche

o nosotros dos, solitarios, desastrados,

yo le exhalaba alcohol,

ella se inclinaba desde su maceta hacia la ventana.

Hacia el final, casi parecía escucharme —

y eso era aterrador—

así que cuando la cretina jadeante de la criada

la tiró, con maceta y todo, al bote de la basura,

no dije nada.

Pero la siguiente semana despedí a esa bruja presuntuosa,

así de solo estaba.

§

The Geranium*

When I put her out, once, by the garbage pail,

She looked so limp and bedraggled,

So foolish and trusting, like a sick poodle,

Or a wizened aster in late September,

I brought her back in again

For a new routine—

Vitamins, water, and whatever

Sustenance seemed sensible

At the time: she’d lived

So long on gin, bobbie pins, half-smoked cigars, dead beer,

Her shriveled petals falling

On the faded carpet, the stale

Steak grease stuck to her fuzzy leaves.

(Dried-out, she creaked like a tulip.)

The things she endured!—

The dumb dames shrieking half the night

Or the two of us, alone, both seedy,

Me breathing booze at her,

She leaning out of her pot toward the window.

Near the end, she seemed almost to hear me—

And that was scary—

So when that snuffling cretin of a maid

Threw her, pot and all, into the trash-can,

I said nothing.

But I sacked the presumptuous hag the next week,

I was that lonely.

*Poemas tomados de All Poetry.

Lectura de cinco poemas de Theodore Roethke («Root Cellar»: 1:49)

Poemas de John Burnside (1955)

Versiones de Alejandro Bajarlia

Enero, 2022